While George Vanderbilt was constructing his gilded Biltmore estate in Asheville, about 250 miles north of him British entrepreneur John Nuttall saw opportunity in the coal rich New River gorge and began buying land and building infrastructure just before the C&O Railway was completed there. His town, Nuttallburg, became the second of more than 50 mining towns in the New River gorge to mine and ship the “smokeless” coal to industrial cities across America. Fifty years later, Henry Ford would lease the Nuttallburg operation in a “vertical integration” quest to gain control of all aspects of his automobile construction, including the coal to run his steel mills. That idea failed and the mines changed hands three times before it completely folded in the late 1950s. All that remains is a collection of empty building, history plaques and structureless foundations hidden beneath trees and vines.

History lesson over. It seemed to us that a trip to New River Gorge would not be complete without a visit to an abandoned coal mine and Nuttallburg was most accessible by the Comos.

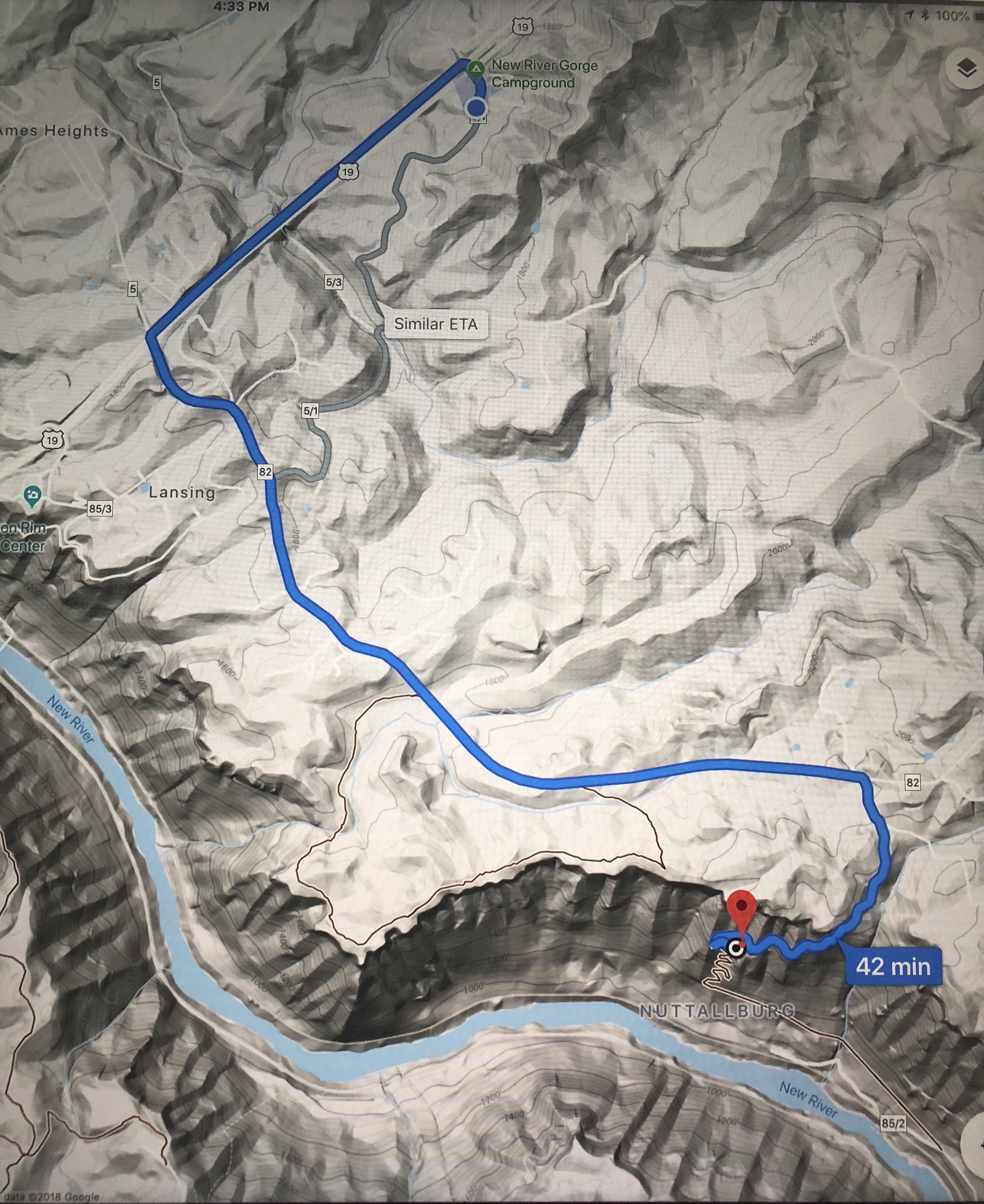

The ride began on Interstate 19 but then quickly transitioned to Lansing-Edmond Rd as we pedaled into the countryside. Within 5 miles, the paved two-lane road had lost a lane and become one of West Virginia’s single lane with wide shoulders back roads. It remains a two way passage but it is understood that should you see another vehicle approaching, both vehicles slow and spill onto their respective shoulders in order to pass. We climbed and descended repeatedly until the final leg down took us into the small West Virginia town of Winona. A dozen or so homes in poor but livable condition marked the landscape. We waved to a couple of old men chatting at their shared fence line and followed an unimproved road along Keeney Creek and down into the gorge.

We perfected the brake, coast and climb routine, mostly in silence as we were stunned by the natural and wild beauty of the surroundings. Large cliffs of shale overhang blocked the sun.

Keeney Creek dropped precipitously forming waterfall after waterfall. We must have seen 50 of them in that stretch. After a few miles of descent, the creek added its water to the much larger New River, the rapids of which we could hear long before we could see the river.

We picked up a foot trail near a NPS marker that seemed like a good shot at taking us down to the rapids. The foot trail crossed the C&O railroad tracks with a thin strip of red tape serving notice to dive back into the forest, which ended at the banks of the New River and Keeneys Rapids, a class IV tumbler we rafted two days ago. We bouldered out to the rocks and perched ourselves next to the rapids as kayaks, and then a set of five rafts came bounding through.

After cheering on the paddlers, we got back on the Comos and followed the New River into Nuttallburg. Along the way, a long train came rolling through with its empty coal cars heading north to some coal rich destination. Nuttallburg, or what is left of it, was loosing the battle against the gorge. The park service had plaques and benches to educate the small number of visitors (we counted 5 people and 2 cars today.)

A large coal chute ran 1300 feet up the gorge and brought coal down to a restored coal tipple. It wasn’t accessible, but it was impressive to follow it with your eyes nearly straight up the terrain. The story of West Virginia coal as told by the plaques was one of good, hard working people, enjoying themselves in this marvel of nature as they extracted energy for the nation. Captain’s of Industry, like Ford and Nuttall, took care of the multi-racial workforce in quaint towns along the river.

What we saw at the “seldom seen” site, looked like the remnants of poor folks trying to eek out an existence in a harsh environment. With rail as the only connection to civilization, the coal miners lived at the “generousity” of the coal companies who set wages in the mine, prices in the company store, and paid in company scrip effectively keeping their workforce in a state of poverty. It looked grim. From what we saw, when the coal dried up no one thought Nuttalburg was a good place to raise a family any longer, despite the natural beauty. It is a complicated story for sure, but clearly one-sided in who the winners were.

After reflecting on Nuttalburg from our 2018 perch, we started our long climb out of the gorge. We took a break for our picnic lunch next to a waterfall with the steep gorge walls in the background. Hydrated and fed, we put the Comos in low gear and tried to use the juice as juditiously as possible. At one point, the road was so steep that we both had maximum electric assist dialed on in our lowest gear. Let me tell you, that is a steep hill. The battery bars on the bikes dropped quickly as we started wondering if they would make it out of the gorge and back to camp.

In the end, we used four fifths of the battery on 2500 feet of elevation change over 25 miles. It was a record for us and the Comos as well as a testimonial for innovation and seeing the world by pedal power.

If you’re interested in more about the ongoing debate over coal and WV, check out this article: The 100 Year capitalist experiment that keeps Appalachia poor, sick and stuck on coal.